Labor Emancipation and Property Rights Formation

|

|

Extant views have asserted that relative factor scarcity is a precondition for private property rights to emerge. Scholars have also underscored the role of the state. Central authorities must have incentives (e.g., collecting tax revenue) to specify and uphold private property rights. For instance, secure and complete property rights in land England were created not only when rising population densities and the commercialization of agriculture made arable land scarcer, but also when the sovereign decided to codify relevant rights and make a credible commitment to them. Yet, in some polities of the New World, private property rights were established when land was abundant and rulers did not have the capacity (e.g., cadastral surveys and land registers) to define landownership.

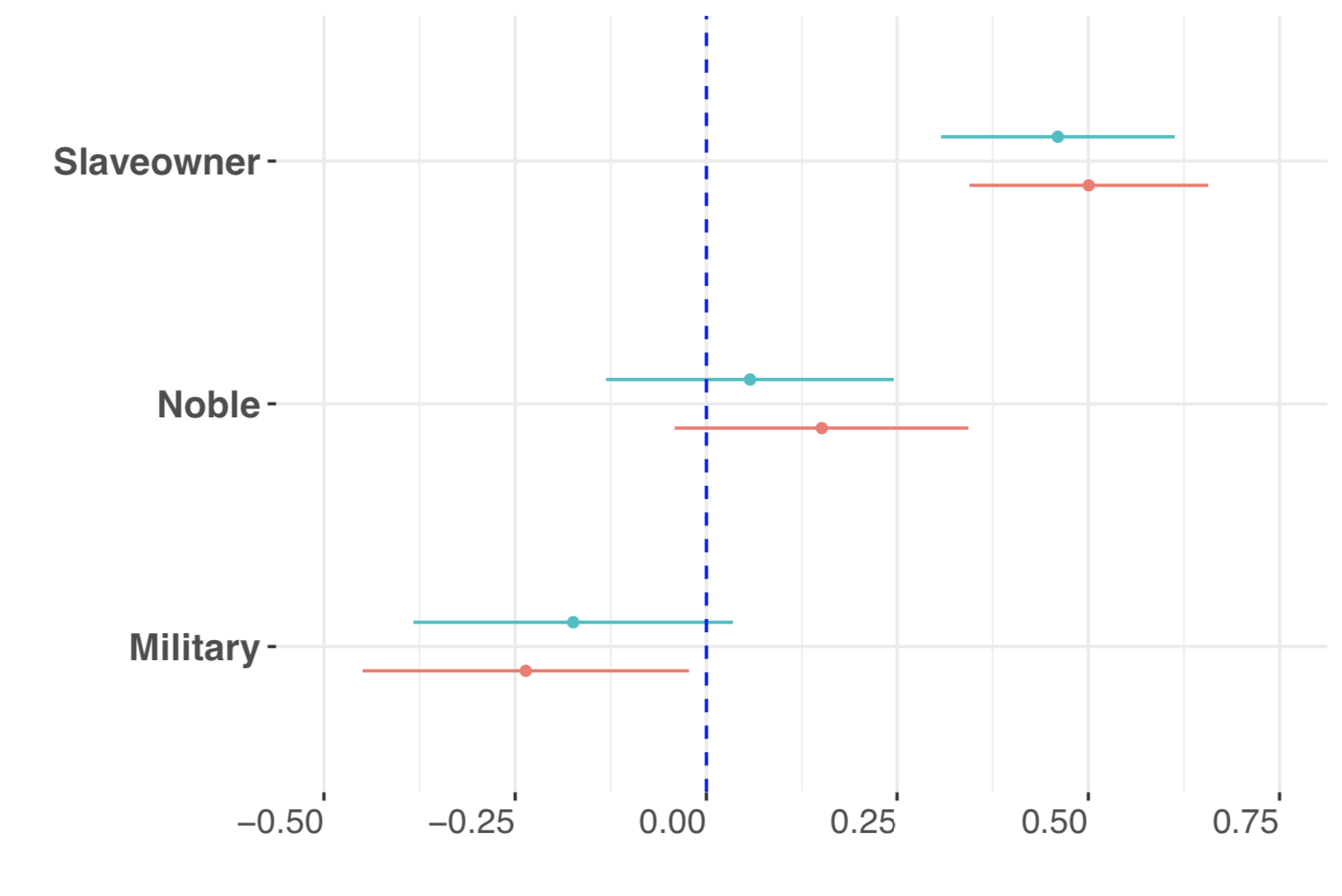

I argue that the exogenous abolition of slavery or the slave trade engenders an opportunity for rewriting the rules of land tenure. Whereas private property entails costly obligations (e.g., demarcating boundaries, paying taxes), it can also supply a cheap workforce. By prohibiting squatting and making purchase the only means by which land can be alienated, private property can generate tenure insecurity and legally reduce the alternatives free workers can find outside agricultural labor. It denies access to abundant land and natural resources, curtails geographic mobility, and suppresses rural wages. As elites comply by recording their landholdings as private freeholds and paying levies, central authorities collect the revenues and documents they need to distinguish occupied from unoccupied tracts, carry out evictions, and implement policies that skew labor markets in favor of elites.

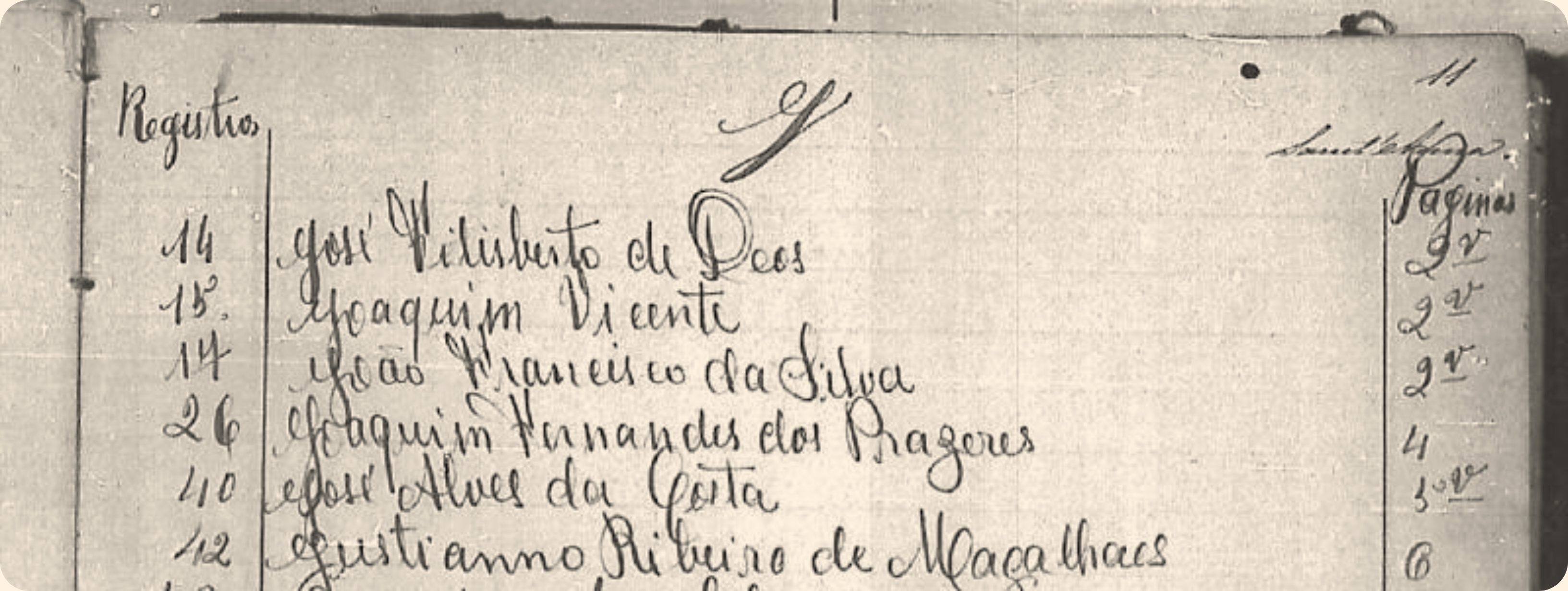

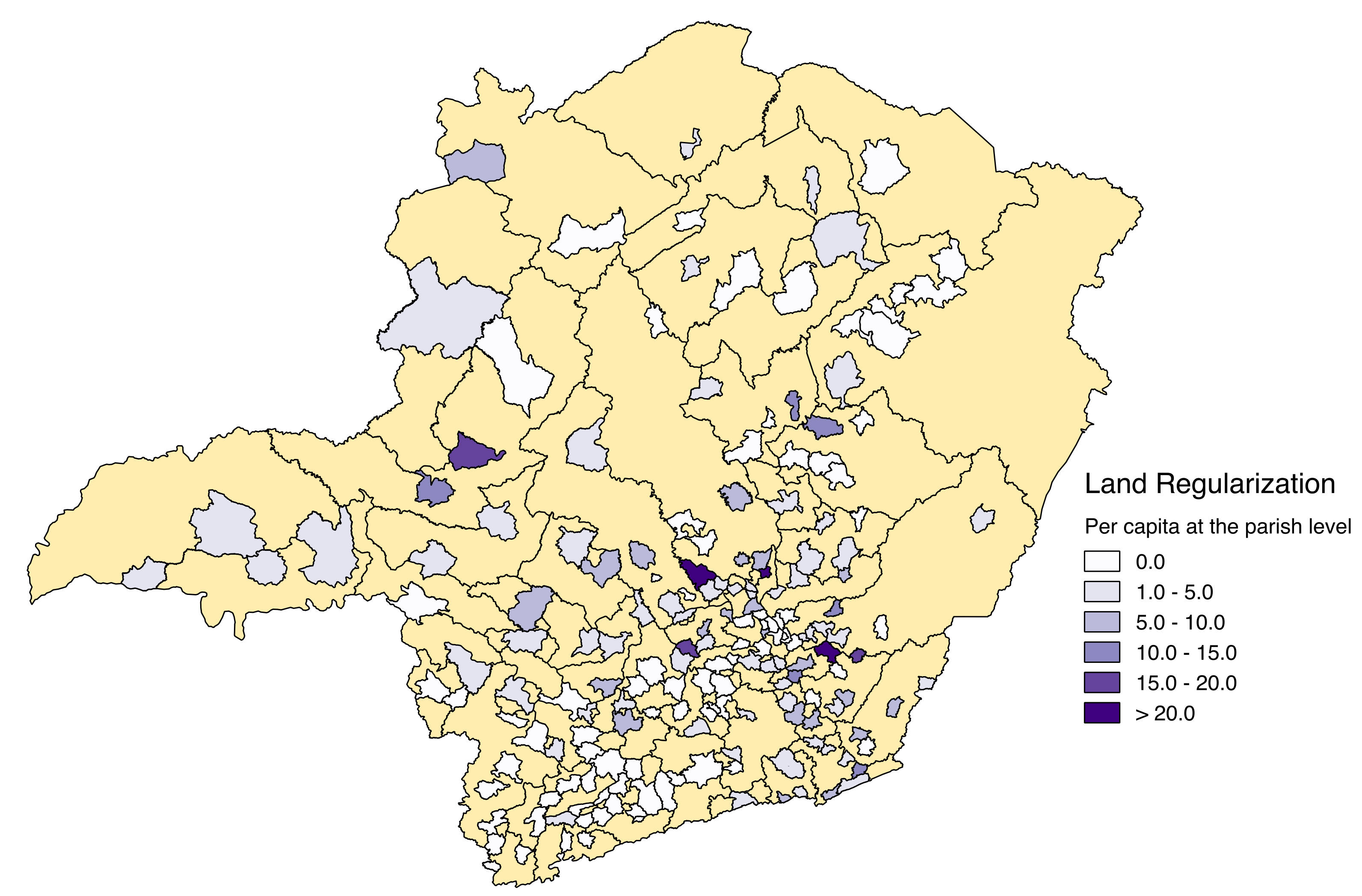

I test these claims in Imperial Brazil (1822-1889), where a British ban on the Atlantic slave trade encouraged a class of planters to renounce their colonial prerogatives over land and support the Land Law of 1850, the country’s first private property law. Planters not only voted for the new law in the parliament, but also voluntarily complied with it on the ground: they self-demarcated the boundaries of their plantations, relinquished vast tracts of fertile land that were under seignorial control, and paid taxes and fees. In so doing, planters provided the resources the imperial state needed to conduct evictions and subsidize the arrival of poor immigrant workers to replace African slaves. I employ unused historical documents that were collected over a year of archival work in eight Brazilian cities, including notary public certificates, slave inventories, and biographical records from Brazil’s prominent elites.